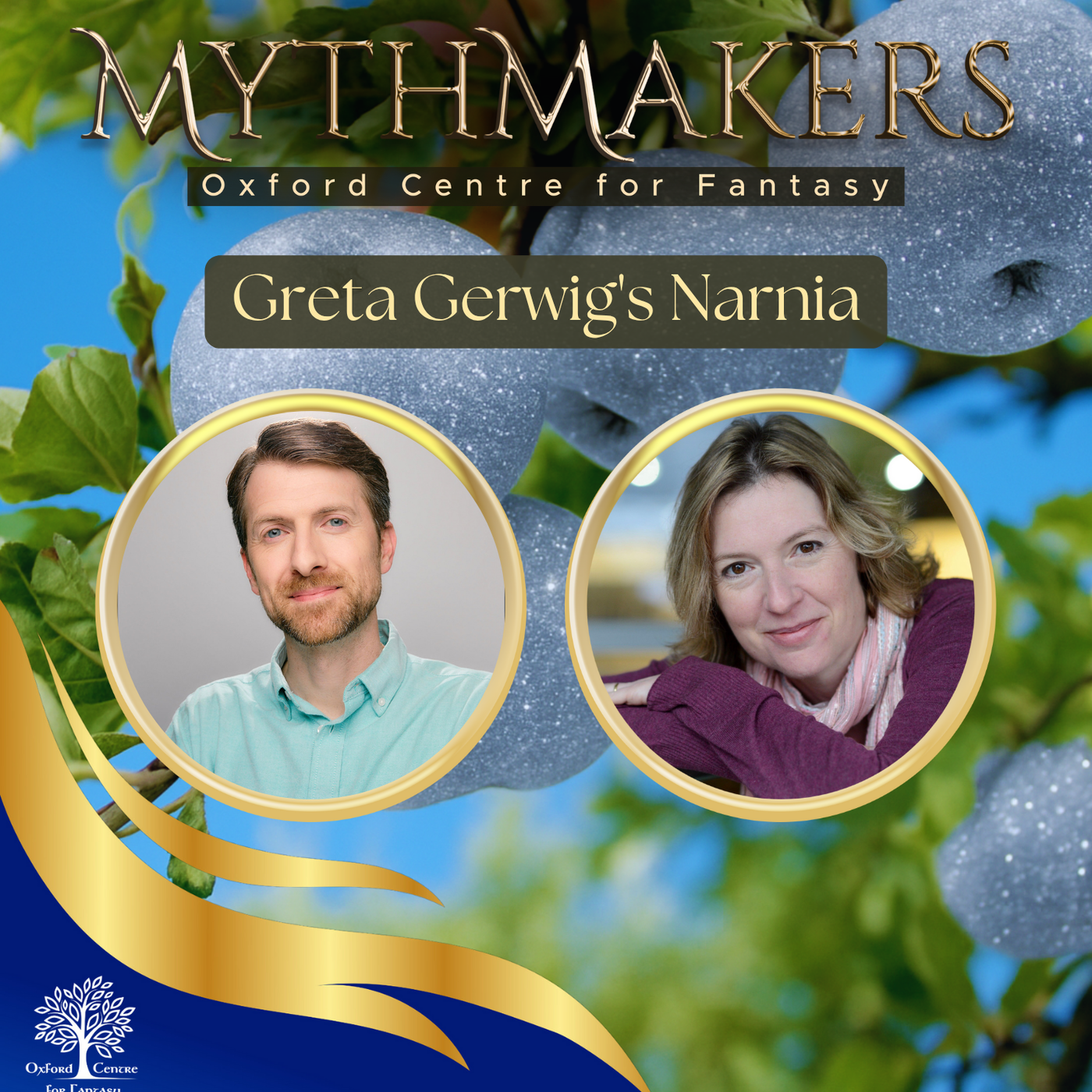

00:05 - Julia Golding (Host)

Hello and welcome to Mythmakers. Mythmakers is the podcast for fantasy fans and fantasy creatives brought to you by the Oxford Centre for Fantasy. My name is Julia Golding and today I am joined by my frequent podcast partner and friend, Jacob Rennaker, and we're going to be discussing Greta Gerwig's take on Narnia and we're going to be looking at the news that's coming out about the Magician's Nephew, which is the film that she has chosen to start with. So, Jacob, first of all, what did you think when you heard that Greta Gerwig is in the frame for doing this?

00:48 - Jacob Rennaker (Guest)

Yeah, I was excited and still am.

00:52

I'm a fan of her work her as a filmmaker, as a creative, I was really.

01:00

I thought what she did with Barbie was very clever and enjoyed that and clearly it was something that resonated with audiences and connected and did very well and did a lot, I feel, for Barbie as a brand as well as a result of the film and engagement and re-engagement with people who played with Barbies as a child and now coming back to something that they maybe had left behind, re-embracing that as a story that dealt with both parents, children, motherhood, what it means to be a daughter and that sort of thing, making it relevant for contemporary audiences and across the board, for male, female equally people enjoyed it. So, yeah, so I think that was something, having experienced that and seeing what it does for treating somebody else's property and an engagement with it, that does something positive for greater participation and investment from a broad variety of people. So barbie's one end of it, um, and her little women I don't know that her, the script for little women uh is, uh is is really great, so I'd recommend anybody out there.

02:16 - Julia Golding (Host)

It's got some pieces. I think in that film, like in barbie, she showed that she really had something to say, and also Lady Bird, which was the uh, and so all of that is quite pleasing. I think Little Women was, you know, the idea of the quadrants that studios are looking for for quadrant films with that's younger women, younger men, older women, older men. I think little women was younger women, older women, barbie, she managed to pull off the impossible Right, make it a full quadrant. I don't know about the older men, but certainly younger men, younger women, older women on what could have been a total cringe fest.

03:01 - Jacob Rennaker (Guest)

Yeah, right, yeah, yeah, exactly.

03:04

So I think, and I think I think, yeah, so, seeing how she's able to to deal with those different, like different audiences and in the case of like a period piece, like with little women, one of the things I appreciate that you see in the script that kind of comes through in like an ambient way or kind of like implicitly in the film itself, is how, uh, seriously, or how much attention she paid to the time period or how thoughtful she was about looking at what is the zeitgeist of this particular period and trying to have that in conversation with the characters that are there.

03:38

So I think she's clearly a thoughtful, very thoughtful, skilled, careful storyteller that has a unified vision, like you said, that that ultimately has all the different pieces working together to deliver a particular you know her particular message. Her vision of that emerged for her in this particular work, given the limitations of the screen, uh, and visual storytelling. So, yeah, so I'm, uh, yeah, an unqualified, like, like excited, um, happy, good to see somebody like that, that is that thoughtful and smart, dealing with the text. That is also thoughtful and smart.

04:15 - Julia Golding (Host)

Yeah, I'd say that she is the most sought after female director at the moment, and for Netflix to have got her for this property means how much they're investing in it. So turn away now if you don't want any spoilers at all. But it does seem that the early indications are that she has decided to set the magician's nephew in around mid 1950s, 1955. Around mid-1950s, 1955. Now there is a reason for this, I think, which is if you turn to the very first page of the Magician's Nephew before everybody throws their toys out the pram. The very first sentence is this is a story about something that happened long ago when your grandfather was a child. So my kid's grandfather was a young, relatively young man in the 50s. So she can turn and say well, hang on a minute, I'm just following the book. The next sentence goes on, to put it firmly, of Sherlock Holmes and Nesbitt. But that first sentence is what has given her that possibility, and I'll just say that my particular theory here is that she's actually more interested in what it would mean for the Lion and the Witch and the Wardrobe. I've got to get this out of my system, because she's doing both films and Diggory is Professor Kirk, who is the man who has the big house in Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. There was a very good film in 2005 of Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, which you'll probably remember very magical. It dealt with very well the Second World War context. It made a lot of that.

06:09

So if I was her coming to this, I'd be thinking what new can I say? Well, okay, if I make it a contemporary story and there's all sorts of things that you can then do. But one of the obvious things you can do, rather than evacuation, you can do a pandemic story. So all these kids are locked away, unable to go out, and sort of revert back to the board game world that we all did in the pandemic. She could do that. My family suggested she could also do a story about modern day refugee kids if she wants to be really right on up there I don't know it's possible like Ukrainian refugee children or something like that, because there was a stage when lots of families accepted refugees from wars. So she's got contemporary resonances that she can pick up on. So, anyway, let's go back to the Magician's Nephew can pick up on. So anyway, let's go back to the magician's nephew. What do you think about dumping the edwardian early, late victorian setting and putting it in 1955. Are you aghast or are you pro?

07:15 - Jacob Rennaker (Guest)

I'm not, I think I'm, yeah, like I. So there's and these are all decisions, right, it's like any, any, any work of adaptation is, uh, a garden of forking paths, right. So you have to make decisions at every turn, and those will eliminate certain possibilities, but you have to make decisions. So the rationale that you just described for maybe looking at language in a wardrobe as a contemporary film, something that's taking place in the modern day, and doing that for the purpose of what does this have to say to our time period? Right, what does this have to say about, um, about belief, about cynicism, about hope, about optimism, about good and evil, even. What does that look like today, instead of of firmly, you know, staying with a period taste, leaving the time period in the book and focusing on that and working that into the story, which is like what you said the previous Narnia film took seriously and said so it's a period, it's not just a fantasy film, it's not just a fantasy, a portal fantasy film, it's a period portal fantasy film. And so when you're adapting any portal fantasy, that's something that you'll have to wrestle with. And in adapting that is, do you take this as the time period in which the book was written for the modern day acts that the part where this fantasy world bumps up against our world bumps up against our world, or do you take the spirit of portal fantasy, which is people from our world coming into the next and so you have to make that decision, and so, in order to differentiate it from the previous film, then I think that's a smart idea to do something that's clearly different. But also, I think Gerwig and you know Gerwig is clearly wants to make this relevant and have something that resonates and has meaning for contemporary audiences, and I think that's, I think that can only be. I think that's a good thing Ultimately, that that updating you although there is because this was written in a particular time period Lewis was setting it in the, you know, early night, like 1900, written in a particular time period, Lewis was setting it in the early 1900s essentially that there are certain elements of the story that are dependent on that, that will need to change.

09:40

But again, any adaptation is a work of translation, which means it's a work of interpretation, and so there are certain things you have to change to be able to make sense and intelligible for a contemporary audience. So I understand it, I'm not aghast. I think great things can be done with that. Like you mentioned, the first sentence of Magista's Nephew is you know when? This is a story that takes place when your grandfather was a little child and when Sherlock Holmes was on Baker Street. So Sherlock Holmes has had several. It's the gift that keeps on giving. In terms of adaptations, right? I don't know how you felt about the BBC adaptation of Sherlock or the American version with still a British lead playing Sherlock.

10:19 - Julia Golding (Host)

Holmes, johnny Lee Miller, benedict.

10:21 - Jacob Rennaker (Guest)

C In the.

10:22 - Julia Golding (Host)

Sherlock and the Johnny Lee Miller, yeah, right.

10:23 - Jacob Rennaker (Guest)

So I'm thinking about the BBC one. Johnny Lee Miller, benedict C In the Sherlock and the Johnny Lee Miller. Yeah Right, so yeah.

10:26 - Julia Golding (Host)

I'm thinking about the BBC one, because I think the American one started to be just like any other detective after a while, because I mean you had many more series and episodes. But the BBC one became quite certainly the early series. It lost its way a bit later on. Anyway, that's a different discussion, though people who like the books might be worried about Sherlock moving the books remain.

11:02

This is like a musical variation right, yeah and I've got a feeling we might have to get ourselves into the headspace where we're thinking about Greta Gerwig's, that this is like a variation, otherwise we're just treading. I think it's particularly a problem with line wardrobe, because that film wasn't that long ago right, and it does make things like colorblind casting much easier.

11:28

If you've got a set of contemporary kids because a set of kids that involve different ethnicities during the second world war, there's all a completely different cultural context. That would be questions will be raised about that whereas now we have blended families we can have all sorts of, and it will just look more modern and we want to get to Narnia. So that's the important point. So I think the setup could just be very lightly touched.

11:57 - Jacob Rennaker (Guest)

Yeah, and I think, and in terms of just the flexibility possible in a reinterpretation or kind of a reimagining, is Lewis you know he was looking at Narnia as a supposal right you know, what if a lion did this?

12:14

He's not saying that, this is like an allegory, a one-to-one allegory for a Christian message, right? He's like you know what, if I'm setting this world up, let's say that there's a figure, that that there's a figure that there is a God, that there is a Jesus, and what if, in this world of talking creatures, how would Jesus appear in this world? How would that kind of play out in that setting? So he called it a supposal. So you can take that same principle and say, suppose, like what if Narnia was set in the line in which the, the Witch and the Wardrobe was set in the modern day? How would that play out? And that would play out differently.

12:48

Just like for Lewis, he wasn't thinking of some like slavish one-to-one correspondence between his own theology, all these different mythological systems. He was kind of putting this together and saying what would these look like? How would they interact? He was really doing what children do commonly with different toys. You know taking. You have your Barbie and you have your Transformers and your Star Wars, and they're freely. You know mixing and mingling and you're telling wonderful stories that can keep children, you know, delighted for hours and is formative to their imagination, but it's not in a rigorous. They're not saying like you can't do this. This character clearly cannot function in a, you know, 2020 setting. This character is actually this knight figure that I have cannot interact with a paw patrol, a contemporary talking animal, right? So I think that his flexibility, Lewis flexibility in dealing with that like imaginative worlds, I think that they're completely accommodated. Now, if you're just that's a different conversation when you're talking about tolkien right um, oh yeah, doing that sort of thing, yeah, organic hole, yeah right, right, right, um, so, so anyway.

14:00

So I think that's yes, but there, but I think there is something. There are things that are lost, and I'd be interested to hear from you, julian, what you think. Items from Magician's Nephew that were Victorian era that you feel were kind of like baked in. What do you think are things that you would lose possibly from removing some of those elements or recasting it, you know, 40 or 50 years later.

14:21 - Julia Golding (Host)

Yeah, absolutely. I think that's a longer conversation. Can we just quickly dip in to the casting?

14:28 - Jacob Rennaker (Guest)

so far.

14:28 - Julia Golding (Host)

Because I think the changes are not going to be so big for the magician's nephew as they could potentially be for the Lion and the Witch and the Wardrobe, coming bang up to date, because the 1950s still feels like quite a long time ago for most of us, and the casting has been very small-c, conservative. I would say so it will look. It's not going to get the outcry that oh, you've cast a different race person to be Diggory or whatever it might be, Because the way they've gone on that is, they've got Daniel Craig as vile Uncle Andrew, which he wants to chew up the scenery, I'm sure, because that's such a wonderful part. You've got Emma Mackey as Jadis. Now Emma Mackey was also in Barbie. She looks very much like. When you see her you'll think, wow, cheekbones, she looks like the illustration, she's got the look. I could imagine her also in another context being Cruella de Vil. You know she's got that, so I'm sure she'll. She'll be great. Carey Mulligan as Mabel Kirk, the mum. So I'm anticipating that she won't just be in bed. I would imagine there'll be some you know, more use of Carey Mulligan than someone who's a deaf store maybe some flashbacks or something.

15:58

And then, of course, the two big are David McKenna, who is Diggory, and Beatrice Campbell, who is Polly. Obviously, as young actors, we don't know very much about them. What we do know, though, about David McKenna is that very nicely actually that he's from Northern Ireland and does have a kind of young CS Lewis stature, because he's a kind of bigger lad, shall we say. He's been cast, and this is going to come out. First he's playing Piggy in the adaptation of the Lord of the Flies which I think the BBC are doing. It's about to come out. So he is clearly already has an extremely much more difficult role actually under his belt, so I'd be interested to see what he does. He's not what I would say, he's quite a British casting, rather than a kind of Disney kid casting, shall we say, and I think that's really good. So I think that the cast will hold it really well together. So do you have any? I mean, I don't know if you looked into them, Okay.

17:08 - Jacob Rennaker (Guest)

Yeah, nothing else on casting other than the group. Yeah, that's good.

17:13 - Julia Golding (Host)

Yeah, going into what you were just asking, and I'm going to ask the question back to you about the 1950s, the immediate thing I thought of was what are they going to do about Strawberry Fledge? Because my favourite illustration from Magician's Nephew is one which so many people remember. It's the one of Jadis riding a handsome cab, acting like this Babylonian queen type thing that she is acting like this Babylonian queen type thing that she is by the 1950s. We don't have handsome cabs of that nature in London. I mean, there are the occasional horse, but by then it's an occasional horse, perhaps somebody on a milk. Yeah, you do get actually just thinking about it. There were a few horse-drawn vehicles, but certainly not cabs. And of course the Frank the cabbie becomes spoiler, the first King of Narnia. So they're going to have to fudge that. Find a way to get him. You want a kind of cockney lad.

18:17

You can't make him a guardsman or someone who would conceivably have a horse. Could be a rag and bone man. Actually there were people around have a horse. Um, right, could be a rag and bone man. Actually that they people were around um of horses at that time. So there are things, as a british person, I'm thinking you could do, but I wonder what Greta's gonna do. Um, so that's one big challenge. I would say. How about you? I will do one each.

18:39 - Jacob Rennaker (Guest)

We'll keep swapping yeah, um, yeah, so that one agreed there that it's tough. You don't have the same impact of Jadis riding a cab on the roof and the salt of the earth, just kind of like hardworking, blue-collar, common person. The point is that it's an unassuming everyday person that is put in as Narnia unexpected everyday person that is put in as Narnia unexpected, rather than somebody, you know, an aristocrat or somebody with the proper upbringing, and that's the purpose and the lesson there. So I'm sure that they find something there. But the question is, yeah, how do they do that? So yeah, I absolutely agree there. Lamp post, right.

19:28

So this is the Magician's Defuse story in general was created, created, uh, because the question was asked. I think it was roger lancelin green that asked, uh, Lewis, when he read, uh, the lion, the witch in the wardrobe, well, where did that? So there was a, there was a lamp post there. Where did it come from? And so Lewis started working on. So the magician's nephew was actually the book that he started writing after laying the witch in the wardrobe, but it was actually ended up being the last one that he finished writing because of the difficulties he found in trying to develop it, and to his satisfaction. So, but he started it because of this, quite in part because of this question is asked well, what about? Where did this lamppost come from? So he had to go.

20:01

Ok, something has to happen prior to this World War II group of children that allowed for this lamppost to be embedded here. What was that? And so if it's coming from 1900s London somewhere, then you have it's a gas lamp at that time period lamp, uh, right at that time period. And so, yes, there could still possibly in that time period from what I understand there could, could be a few remnants of gas lamps being used during that time period, but the by and large, things have converted to electricity I reckon I'll just fudge that, because yeah, probably, because you know a flickering, because those kind of traditional lampposts do exist in London, because it's a city that visually likes to keep its sense of continuity in age, as does Oxford.

20:56 - Julia Golding (Host)

So you'll see those lampposts around, not all everywhere, but some of them. So I think that would be okay. I think thematically, just sort of digging deep deeper. What is clear about the interaction with charm and 19th century late 19th, early 20th century London is Age of Empire stuff. It's a bit subtle for a kid to pick up on, but certainly as an adult reader, this was the heyday of the British Empire.

21:34

There is a message in it about Chan being the last. She ended Jadis, ended her empire, had a battle with her sister, spoke the deplorable word, killed everybody. So she's collapsed an empire and she's moving to London, thinking she can take over, and then finds that her magic doesn't work but she's still very strong. So she's sort of like a giant type figure really, and so she still does pose a threat, but she wouldn't have been able to take over. But there's a warning in her that makes sense to bring to London.

22:18

And now thinking about what's happening in 1955, it's a decline of empire. It's the battered London of post-war britain. Um, rationing has just ended. Um, you've got a young queen on the throne, so there is a revival happening which leads into the sort of 60s where things pick up again, but it is, you know, the l, the London would be that of, not that dissimilar to Chan. It would be bomb sites, and you can actually use that though, I suppose.

22:52

But the feel you're moving from high heyday to decline and it changes the themes of the book, which you may lean into, but you are using something lean into but you are losing something, because of course the whole Empress Jadis bit is actually a nod to the Ines bit, a story of the amulet episode where a queen of Babylon comes with the children to claim all the goods in the British museum. It's a wonderful book and she just she sums every, all her own stuff out of the museum and it all starts pouring out. It's a really fun episode. So Lewis has got that which he would have heard as a youngster himself. He's got that in mind when he's writing that. So there are some connections here which will go because of the change in time.

23:49 - Jacob Rennaker (Guest)

Yeah, and that's interesting. We're talking about a younger queen on the throne. Jadis is kind of seen as like a foil for Elizabeth.

23:58 - Julia Golding (Host)

You could do all sorts of things with that, couldn't you? Yeah, it was the queen when she was at her most, the late queen at her most fashionable. She and Prince Philip were quite a glamorous looking couple. I don't know that they'll find time for that, because, of course, it's not going on in that scene. But, it is a possible nod that you can do there, yeah.

24:23 - Jacob Rennaker (Guest)

Yeah, and when you mentioned a churn and the deplorable words, that's another aspect, that is, it was impactful in the book and I imagine to readers at the time is, you know, seeing the deplorable word is this kind of essential weapon that is deployed to essentially wipe everything out, so on every side of it, right, right, right. So the people, so, while in so in, so in so readers, adult readers who are reading that at the time when it's published, you know, read that and clearly would probably have an easy time making that connection and saying, and I can see that being kind of a profound, you know, lesson moment there for some adult readers, but not for the children in the story. Right, for children in the story, this is 1900. So this is, you know, decades before the atomic bomb is even an idea, and so it doesn't have an impact on them as the children. They just think that this is there's something that's big and bad and can happen, and it's vague in general. But in here, in changing the time period, what you can have is that lesson uh being kind of comprehended by the children themselves, which is something that wasn't possible in the original, uh, you know, historical setting. So that again it's it's different, it's a change, but it's. It's something that could potentially have a resonance with the actual characters themselves and that changes degree. So a degree, um, who is post-war, who is aware of atomic weapons and that.

25:54

And then seeing charn and maybe making that connection himself and what that does to, then, if you bring him into lying the witch in the wardrobe later, where he's aware of exactly he's seen in his own world what charn is, is what the deplorable word is capable of in our world, um, it's not just a theoretical, this is a big bad thing that could happen. He says like, oh, this sort of thing happens in our world and it's just as bad as what's in Narnia. And so Narnia in some cases might be seen as more of a threat to our world or more the possibility of peril. And if Jadis is coming back through the wardrobe into our world, that's probably going to become more real If she does this to that world. This is, in a localized way, happened in this broader world that Narnia is attached to. What can she do now in our day?

26:49 - Julia Golding (Host)

She doesn't, but it's made. She does try and use a deplorable word or a spell on Leti, doesn't she?

26:59 - Speaker 3 (None)

And it doesn't work.

27:01 - Julia Golding (Host)

So in our world she doesn't have, she's got strength, but not magic, whereas in Narnia she has magic Because, you remember, she goes around sending people to stone.

27:08 - Jacob Rennaker (Guest)

Right, yeah, she has that. Reducing power, right, yeah, that's a good point. I know another question would be like so if Jadis is still back and functioning she's had this so much time she's had, in Narnia time, far more time to be able to has she found a way to recover that sort of magic or find a way? Has she been working to try to bring magic back into, or her magic into, our world? Who knows? But that's I can see. I can see a degree that the child, having witnessed what is possible with with not just bombings but also the atomic bomb and the news of that and what that would have looked like to a child, then that affecting and having lasting emotional memories coming into the present day and how they see then a revival of this magic and probably flashbacks to what they experienced themselves as a child. So, yeah, I think there's again, there's trade-offs for changing that. But I think there's trade-offs for changing that. But I think, regardless, since war is still something that happens in our world today, I think that's still going to be just as relevant.

28:13

This warning about empire power. How do you use weaponry? What does it mean to possess something? What's our relationship with creation? A stewardship over creation?

28:28 - Julia Golding (Host)

She might have her eye on America, you know, because in terms of the stage America is in it's world power, are you the same as the UK was back in the 50s? Discuss, Anyway, another theme that is coming into the frame is the big one, which is about the central story about getting a fruit that will heal your mother of what looks like cancer. Philip Pullman is pretty irate about this. He really dislikes famously dislikes this book and dislikes CS Lewis as well, and this is the bit that he particularly dislikes, because he thinks that Diggory is being rewarded, that good boys can cure their mother, which is a terrible message to give to boys whose mothers and girls whose mothers do die as tragically, people do, unjustly, just because that's the way things happen. What do you think the story is going to do about that? What would you do?

29:42 - Jacob Rennaker (Guest)

Yeah, that's a good question and I think and I think that's, I think that's, I think it's a fair point in that, like you don't want, children are impressionable and it's often, uh, children. I know I'm heartbroken when my child thinks that something is his fault, that he that is not his fault, something larger in the world or health wise, or something somebody got hurt, uh, and he feels like he's responsible for it and just like how, how much that troubles him as a more sensitive child. So I totally get that. I absolutely do not want that, wouldn't want that to be a precedent for children, and so you do have to be careful about being mindful of the lessons that children are taking away.

30:30

On the other hand, though, magician's Nep nephew seems to have been probably the most autobiographical of the Narnia chronicles, for Lewis right. So he's his. His mother died, and this is in some ways, a reimagining of his own childhood and a way to, in some ways, almost like redeem the memory and experience that he had as a child and to give him hope, or maybe this is something that he wished, a sort of hope he would have had as a child, writing it for baby Jack, something for him. So if it's. In some ways I could easily see that as Jack feeling like he should have been able to save his mom because he was being a good boy, and in that case this is actually giving a validation for a reworking of that, that mentality, but then providing himself with the sort of wish fulfillment that like, okay, but it actually. But it actually wasn't because you were a good boy necessarily. It was only because of aslan and this other world and something that was completely outside of your control, um, that that then was able to bring healing to her. Um, in that sense, so it wasn't ever necessarily about degree, but it was about aslan, what aslan could provide.

31:48

So you can interpret it and see it that way, which is is more resonant with Lewis's Christian worldview and how you actually save people from death. There's nothing that humans can do and it's foolish to try to extend life ad infinitum. But because of that you just become a monster, presumably the longer you live and the more that you have the vicissitudes of life. And if you're just hanging on and grasping at life, there's a root desire there that isn't reconciled with larger ideas that he believes in his Christian outlook that humans should be more attuned to. It shouldn't be about life in terms of longevity of life, but rather the quality of life and how you're helping other people to flourish in that.

32:35

So anyway, so I think it's in some ways, if you see it as Lewis, this particular aspect as Lewis, kind of working through his own childhood and providing hope for maybe not just for himself but for other people and something in difficult situations, I can see that being a false hope from Pullman's perspective. But also from a different perspective, I think any hope, any sort of relief or light you can give to somebody that's in a difficult situation can be if it's done sensitively and it is clear that this is a work of fantasy, uh, and not necessarily a direct, you know, correlation to what's actually happening in the real world. I don't know, what do you? What do you? What do you think Julia?

33:25 - Julia Golding (Host)

I think CS Lewis has every right to tell this story in the way he wants to tell it. It's a story written for younger children, which is about magic, and even a younger child will realize that this is a magical event, not an everyday event, and it's the magic that makes a difference. Good moral choices help, but it's not because he was good that the magic apple that he's given the magic apple, because he was good that the magic apple that he's given the magic apple, because he makes good moral choices. Um, he doesn't take it for himself and so on, and that's perfectly fine as a story to tell, and there are plenty of happy, ever after stories out there which follow a similar thing.

34:08

If you want to read a story which deals with the, the death of a mother and the um and the role of a child, you you read a monster calls monster calls absolutely remember.

34:21

that is a ya, that's a book for ya. When children are older, children are able to cope with complexity. There is nothing wrong with saying, in this magical tale, this boy, because of his bravery and courage, is able to make up some things. He did wrong and he gets this magical artifact, this lovely apple, which helps his mum. That's fine, I think it's probably more. I think, with Philip Pullman it's more an annoyance that he's always compared with CS Lewis and obviously, temperamentally he probably wouldn't have got on, let's face it, and I think he's kind of fighting a battle on this one. If I was him I would say that's not how I would write the story and leave it at that, because there's nothing wrong. I like happy ever after stories and I'm fully aware the world isn't always happy ever after and I was aware of that as a kid.

35:27

So, I think it's fine to have a lovely family film going to the Greta Gerwig thing where you don't have to say, oh, by the way, lots of other people are dying. I mean, fine, but that's not how. The film isn't really about that. The film is about his choices and after he's made some mistakes, and it would be awful if at the end, after doing the right thing, he gets home and his mum dies. I mean, just think about that, you know.

35:58 - Jacob Rennaker (Guest)

Right from a child. Yeah, the child seeing that. No, that's good, and I think and that reminds me of right, with GK Chesterton writing about, you know, critiques against showing, you know, dragons or monsters to children that children shouldn't see sometimes the scarier things in life monsters, specifically or bogey is the phrase that he uses and he says something along the lines of children are going to see monsters anyway. What a child is thinking about in terms of what is bad and worse and scary, it's probably far worse than any adult could write. Uh, what the adult would be writing would probably pale in comparison to the imagination of a child. Um, what the importance is not showing, that is, is making clear that dragons exist. Um, it's to show that dragons can be conquered in some way. Right, it's to give that sense of hope that, yes, the world is scary but there is a way forward in that world that does have hope and light and you can carry that with you in spite of the monsters and everything there.

37:05 - Julia Golding (Host)

So I think that that's what the story does right and also in defense of CS Lewis. He's anticipating quite a lot of the breakthroughs in modern medicine, because his own mother didn't have any of the treatments that are available to a woman in the 1950s or, and certainly not today. So you can do it. That the magic apple is is like you know. It's like aslan's form of chemotherapy. People get better from cancer. They do. Thank God that they do. They're in recovery. So you could, if you wanted to sort of fudge it a bit. You could have a little bit of that context if you were Greta Gerwig who was worried about this, but maybe she won't be. Anyway, it's just out there as a critique of the story, so I thought it worth raising. So do you have anything else you want to say about this, or shall we park it there? You know, tie up our handsome cab at this point in the conversation. Yes, tie up our handsome cab in 1955 London.

38:06 - Jacob Rennaker (Guest)

We'll wait to see what they do. Yes, type our handsome cab in 1955 London.

38:12 - Julia Golding (Host)

We'll wait to see what they do.

38:13 - Jacob Rennaker (Guest)

Next to the car, next to the yeah, next to the car. So you know, I think this is great and it's tough and one of the difficult things it can be difficult in talking about something where there's so little information about in terms of a film and you haven't seen, you know where there haven't been like official photos, like official promotional materials and things. It's just kind of hearing rumors and kind of extrapolating, which is fine. But the most difficult thing is, I think, like making is keeping observations, everything we're doing tentative until you can see what the final product, what's happening, what's she doing, how is she doing it? Some of the things that your pictures that you're seeing might not even appear in the final cut of the film.

38:54 - Julia Golding (Host)

Yeah, they may be just pulling the wool over our eyes and actually doing a really good treatment. And then, when we look, through it. That's fine, I can take it.

39:05 - Jacob Rennaker (Guest)

So it is fun to kind of think through the different ways as a creative right. So what could this mean story-wise? Keeping it tentative and uh, knowing that, like we can, you can like the. The book exists and will always exist in the form that it is, um, and so nothing can touch that original idea and your relationship, your individual relationship with the magician's nephew, as written by and uh c Lewis and illustrated by Pauline Gaines. That will always exist and you can maintain that you can, as a creative or as a fan can do the same thing, like what's the movie that you would make?

39:41

How would you reimagine magician's nephew in this day? Or even if you were to put it in the future? Or what if you were to put it in a medieval age right? So there's all sorts of things that you can do as thought experiments, storytelling-wise, that I think can help hone our own storytelling muscles and tools that we have as we engage with other people's stories and appreciate what they're having to consider as a creative that can reflect our own storytelling, I think, in a really significant and positive way.

40:12 - Julia Golding (Host)

Thank you, Jacob. Thank you very much for discussing Magician's Nephew with me.

40:18 - Jacob Rennaker (Guest)

Happy to be here.

40:24 - Speaker 3 (None)

Thanks for listening to Mythmakers Podcast brought to you by the Oxford Centre for Fantasy. Visit OxfordCentreForFantasy.org to join in the fun. Find out about our online courses, in-person stays in Oxford, plus visit our shop for great gifts. Tell a friend and subscribe wherever you find your favourite podcasts worldwide.