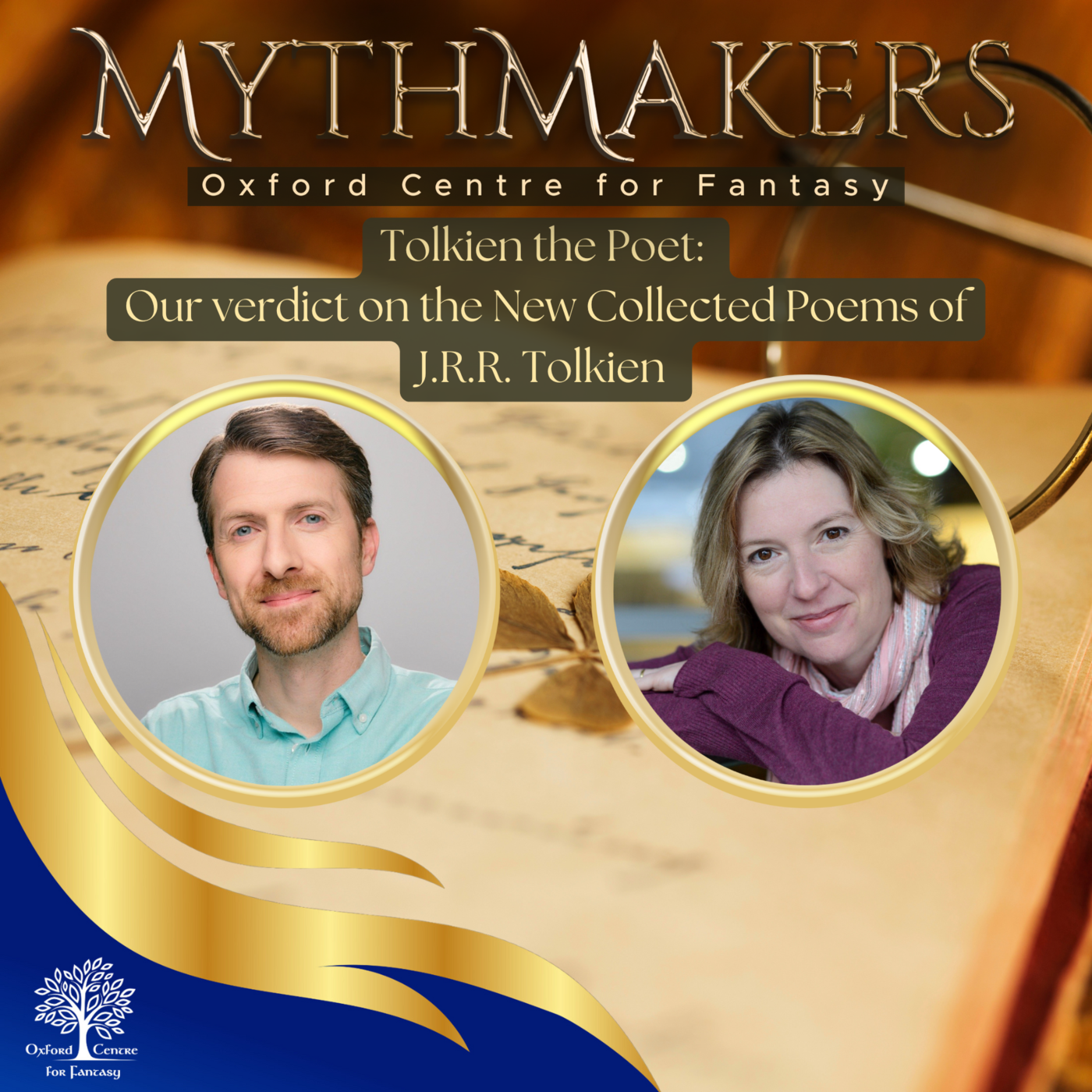

00:05 - Julia Golding (Host)Hello and welcome to MythMakers. Mythmakers is the podcast for fantasy fans and fantasy creatives brought to you by the Oxford Centre for Fantasy. My name is Julia Golding. I'm an author and a passionate fan of all things Tolkien, and joining me in that enthusiasm is my podcast friend, Jacob Rennaker, from over in America. So welcome, Jacob, to our discussion today. 00:33 - Jacob Rennaker (Guest)Thank you. 00:34 - Julia Golding (Host)And what we've decided to take on is Tolkien the Poet. Now, this was inspired by the publication of this wonderful box set of the collected works of Tolkien, which has been put into three sections. They go from 1910 to 1919, then 1919 to 1931, and then the final volume is 1931 to 1967. Uh, so, for example, the 1919 volume includes some of his war poetry, more about that and on um. And then the last volume contains all the stuff that you know from lord of the rings, and the middle one, um, 1931, is actually a sort of emerging Hobbit-y style and Silmarillion poems I would say. Anyway, there's plenty in there. 01:34I would say that probably only the absolute diehard Tolkien fan will buy the three volumes because they are not cheap will buy the three volumes because they are not cheap. But if you can get hold of a copy in your local library, I would particularly recommend where to start. I would particularly recommend going straight into poem 149 to 171 in the third volume, which is all the Lord of the Rings stuff. Once you've got that under your belt, which is all the Lord of the Rings stuff, once you've got that under your belt, you might want to pop back into poem 128, which is the fascinating Errantry poem, which we might spend some time talking about. And then, if you want to think about the war years, go back to poem 58, which is called the Brothers in Arms. All of these are fabulous poems, anyway. So that's the headlines, and now we're going to have the discussion about Tolkien the Poet. So, jacob, what did we learn about Tolkien the Poet by having a look at this three-volume collection? 02:43 - Jacob Rennaker (Guest)There's quite a bit and, like you mentioned, this is an incredible piece of scholarship and the notes, the footnotes. So I kept it. Took me so long to get through it because the footnotes and commentary were so fascinating, pulling in elements from to provide full context from letters, which we've done a previous episode on the newest edition of Tolkien's letters, so finding all the places in there where he's talking about writing poetry, his approach to poetry, why he even wrote poetry in the first place, and one of those. I think for me, as you asked about Tolkien the poet, there was a section from letters that I think sets up why he explained why he wrote poetry or when he started writing poetry at the beginning. And he said, talking with one of his friends outside of a cathedral, and his friend asked him why is it that cloud? Well, so Tolkien asked his friend, why is it that cloud so beautiful? And his friend says because you have begun to write poetry, john Ronald, assuming that his writing of poetry is opening him up to sing the world more beautifully. 03:59But Tolkien says he was wrong. It was because death was near and all was intolerably fair, lost, air, grasped. That's why I was beginning to write poetry. So for him it was this sense of it wasn't poetry that's helping him see the world as beautiful and fragile, but rather he saw this fragile world and death all around him, and so his response to that was poetry, was putting that into words and kind of recording that. So I think that's a fascinating kind of like. Starting point for him was death, which we see as a major theme in Lord of the Rings, right, you know, death loss. And yet there's something that we see throughout here, this inevitable kind of upward turn, this kind of eucatastrophic turn in his poetry and in the development of his poetry to hope amid this loss and death. So something that kind of initially kind of stood out to me. How about you, julia? What sort of things kind of initially grabbed you looking at Tolkien as a poet, kind of initially? 05:02 - Julia Golding (Host)grabbed you looking at Tolkien as a poet. Well, we must shout out. Talking about the scholarship, the editors it's Christina Scull and Wayne G Hammond to whom we owe all this wisdom. So well done, guys. It's been obviously a labour of love. 05:20So, yes, I agree with what you're saying and, of course, death was one of the themes that he explicitly said was behind Lord of the Rings. On many of his number of things he says Lord of the Rings is about, and that's one of them, I think. Also for me, looking at the poetry is just how much there is of it. During his life. He carries on writing poetry right up to 1967, so right up into old age. There are particular moments which are very fruitful. So particularly his youth, when the group of his school friends got together and poetry was the thing they were sharing predominantly between them. Sadly, as many of the listeners to this will know, that most of that group, or half that group, was wiped out by the First World War and that was a sense of the loss of the poetic voice of that generation, that Tolkien's kind of stepping up to be for them. And then, of course, the 20 twenties. Lots of poetry there, uh, and then when he's writing his books, um, he is writing for particular narrative moments, so there is a lot of it, um, and the archive on it is extensive, so it's not just the. 06:43The reason why there's three volumes is because they're putting all the different versions of a poem down that they could recreate from the manuscripts. So it's not an easy read, it's a scholarship read. So sometimes, if I was less interested in a poem, I would skim the various versions and go to the final version, and then we'll look back to see to follow the narrative. So I think you can dip into this book in any way you like, um, and I was trying not to get weighed down by the scholarship. I'm not writing an essay on talking, so I allow myself to enjoy the poetry as being poetry, um, so that there is a lot of it. Then the next thing I would say, my next headline, is how much he experimented and played with verse, and this is a constant theme. What did you think about his experiments with nursery rhymes, for example? 07:39 - Jacob Rennaker (Guest)did you get those ones? Yeah, he. So when you know he says in that, in that quote, that it was death, you know that really inspired him to poetry, um, but that wasn't the only thing that drove him. I'm sure that was an element, or at that time, looking back, he saw that as a as a major influence. But when he became a father, right, that's when he starts reworking these poet you know these, these, you know nursery rhymes, writing a few little verses just for his, his new child, right when he, when john uh was born, uh, he just started writing this poem, a rhyme for my boy, um, that's just about somebody getting a little crown and buying it in the market and just, it's just, it's little, it's silly, it's quaint, uh, but it's, but it's cute. 08:20So you see him really kind of playing, like you're saying, like playing with language and with the nursery. So you see him really kind of playing, like you were saying, like playing with language and with the nursery rhymes. You see that all over the place, right. So he's, I think you see him in some ways he's participating in the tradition and so this is something that like kind of comes up later and we'll just this is a kind of a teaser for talking later about some of the poems that are in the Lord of the Rings, especially the poems for Rohan, that are more patterned after Old English. He's not just aping Old English poetic styles, he's using those as jumping off points and putting them in conversation with the original poem. Because in one of the footnotes, um, it mentions him kind of chastising uh other translators for trying to make the poem's message more palatable to contemporary uh experiences and expectations for poetry, and he says that that was an act not of like translation but of destruction that you need to like let these things stand on their own and give them their full voice. But it's okay. He took full liberty to say like, hey, I would I'm consciously taking this poem as kind of my sparring partner and he would then, you know, play with it, so, like with the cat and the fiddle, which then later becomes, you know, the man in the moon. Stayed up too late. 09:53He takes this little simple children's rhyme. 09:56He's not saying that he's going to like replacing it, but he does, you know, spin a larger tale out of it that fits completely within the world of that original poem, but he is constantly, you know, looking to it, coming back from it, and this kind of interplay between these pre-existing ideas and him, like you said, just having fun and playing and kind of expanding, using his imagination to kind of encourage this poem to flower in a way, by his participation and engagement with it, that it's in fact honoring in some ways that original kernel of that poem. 10:36He's respecting it enough to take it seriously and to develop it. So that was something that is really fun to see him doing there and that, of course, I think fits in with his larger project of, you know, sub creation, right, taking ideas, things that exist, and then really shaping them into something different, consistent, coherent, that is as lifelike as possible, which includes comedy in addition to, you know, drama and and tragedy. Um, yeah, how about you? What was, as you're reading some of these more playful poems, what were things that that, uh, that you noticed? 11:10 - Julia Golding (Host)yeah, I was. I was drawn to talking about the playful poems because that is a thread that goes all the way through. So he starts writing these when he's a young father, um, sort of playing around with the idea of the nursery rhyme having a sort of bigger, and then he reworks some of them to fit into the Hobbit and the Lord of the Rings. When he needs a poem, so he goes to his drawer of his notebook of poetry and draws them out and shifts and changes them to fit the context. And then, of course, later on he puts together the Tom Bombadil collection of poems, where some of these get reworked again and he blows off the dust of some others that he has. So and then of course he does publish that volume of poetry during his lifetime. So I would say he hoards poetry like a dragon and polishes them up for display at the right moment. 12:08We should also mention we probably won't go into detail about this because I don't think either of us speak Anglo-Saxon or Elvish but there are long poems written in other real and invented languages. The thing about the connection between his interest in languages and his interest in poetry is sound, that they sound wonderful even if you don't know what they are saying. The translations provide a wonderful insight into what's going on, but in a way you don't need that, because it's the sound of them that is so intoxicating. And that is something which he did, both professionally. There were some attempts to encourage students of the of these languages by writing new poetry for them in it, but also, um, what you were mentioning about sparring with them and creating his own and, of course, exploring the possibilities of elvish in in verse. 13:14So there's that area in the book as well. So if you're interested in this um, do dip into those sections of the three volumes. By the way, it's very clearly signposted. Each volume has all the poems listed at the beginning. You just need to look down, find the one you want to follow and go to it. It's very clearly signposted. Anyway, what I want to talk about now is how so many of the poems of that early period start in one context and get dragged into the Middle Earth context. I've got a couple in mind, but was there any where you followed the footnotes and thought this is a really interesting evolution, giving insight into his thinking? 13:57 - Jacob Rennaker (Guest)Yeah, the earliest one that, really, where I realized that this was going to take me a lot longer than I thought it was, was getting into the thick of the footnotes for the Grimness of the Sea, later titled the Tides, later titled Sea Chant of an Elder Day, finally titled the Horns of Yilmir or Olmo. So you see, it's a poem that starts about just his feelings about the coast and the ocean against the shore. That's what it initially was, a poem about a song of 74 lines that Tour makes for Arendelle. So it goes from just musings, kind of just capturing his feelings staring at the coast, to then being fully incorporated into his legendarium in this epic poem. Essentially that's fully embodied by some of the characters that he's created here and actually done in their voice and from their perspectives to fit consistently within his larger legendarium. So that was the one that for me, kind of changed. You see it, no pun intended ebbing and flowing, uh, from his between all of these different versions and all of the different individual you know, strike throughs and and, um, you know edits and reworks, um. 15:36So that one that was probably the one for me that was the earliest on that just kind of signaled to me like, okay, here's, like you said he's, he's hoarding these ideas that he has. I don't know if, like hoarding, I'd say maybe I love that image. I'd say for him it's kind of like cultivating If gold was living, which the dwarves would say it is. So I don't want to say that gold doesn't actually have life, but it's. You know, he's kind of storing these away and like bringing them out, not just like to polish them, but to kind of like water them and see if there's something that he can add to or join to this larger kind of organic organism, uh, this world that he's creating. 16:20Is this something that he can transplant from this original context? And will it survive if, given the same rain and life and by the same sun that he's been experiencing his whole life? And so I think that's why he sees it as that he could just rifle through his file cabinet and say here's a poem about any of these things and he would actually look at it and take it seriously as something that could possibly fit in here. And so that was a fascinating this, this grimness of the sea going to the horns of yilmir, uh, transformation as kind of his process of trying to get his mind around his whole life and his whole, uh, you know, creative identity as a creator, uh, sorry, as a sub, as a sub-creator. Um, yeah, so that's probably one for me, I don't know which ones for you were fascinating. 17:30 - Julia Golding (Host)yeah, another one in that early batch is one called the trees of cotirion which is based on the real city of warwick. Now warwick is, um, it's probably about 50 miles north of oxford and would have been a place that he he certainly visited or met his wife there during the sort of war years, that early stage of the marriage. It was one of the places he was near. So it was very special, beautiful place for them and it is a very beautiful city. It's got a fabulous, absolutely jaw dropping castle. So all very beautiful city. It's got a fabulous, absolutely jaw-dropping castle. So all very mythic. 18:07But what I think is very interesting about it is watching how a real place and a poem about a real place that you can identify and visit morphs into a city that could feel it's part of the Silmarillion and Middle Earth. So if you want to watch the alchemy that goes on in a creative mind, watching the evolution of that poem is particularly interesting. And a very small touch is poem number 83, which eventually becomes Sam's song about the troll, and you can notice the subtle differences that happen in this song, which begins as a kind of comic verse, and the reference in it that particularly drops out is churchyard, it becomes graveyard. If you know the poem, bones were found in the graveyard because Tolkien takes out references to organized religion. He doesn't want to have a sense of you know, after Christ, he wants to be back in the day. So little touches like that. And plus, the troll undergoes a change, undergoes a change, so it's the. It feels more in tune with how trolls appear in lord of the rings and the hobbit than in traditional fairy tales. So it's sort of he's pulled into his the gravity of his sort of planet of middle earth. 19:37Um, so yeah, I think that's one of the things I learned watching this. Uh, it's almost like little versions of the evolution you can find by following the many extra volumes of Tolkien's work published by Christopher Tolkien. You can see small versions of this happening in poetry, which you see in the prose that's edited by Christopher Tolkien. So I think it's also a place where he puts his deepest thoughts. And before we move into the Lord of the Rings poetry, I thought we should do a shout out for poem 136, which is Mythopea. Jacob, tell us about Mythopea. Why should we all go and read that one? 20:21 - Jacob Rennaker (Guest)Yeah, well, this is a distillation of Tolkien's understanding of the myth-making. 20:30Mythopoeia literally means the creation of myths and his whole philosophy of sub-creation. So it's a really great companion piece for his lecture, his Lange lecture on fairy stories, stories later turned into an essay. So you kind of, if you, if you look at mythopoeia in conjunction with on fairy stories and Smith of wooden major, all three of those are kind of this Trinity that really distill and illustrate in different ways what Tolkien sees himself participating in when he's writing and the utility of that. And to use the word utility is something that he would spit at, and so it's not utilitarian, right, it is celebratory, it is and in some cases devotional, because this is something that he's fitting within his larger religious framework as well. So, yeah, so mythopoeia, and this is something that's particularly dear to me I think this is the first Tolkien poem outside of Lord of the Rings that I read and I just fell in love with, as I was kind of trying to understand his philosophy and his theory of myth-making. But it's also when I was with you, julia, at Oxford and this is a heist of recommendations for courses that you can take through myth-makers yourself, julia was able to show me, at Magdalen, uh, at modeling college, uh, the little path where this is a poem that's kind of spinning out of a conversation that Tolkien has with uh, cs Lewis, that said, a specific, you know specific place. Julie can show you exactly where, uh, uh, maybe not the moment where this actually hits, but the you know the, the place where they're, where they're walking, um, that that Lewis, um, uh, hugo D, hugo, dyson and Tolkien are kind of talking about myths in general and why they're valuable. 22:34This is the one that kind of starts with. Before the poem starts, it says you know it's from essentially Philomythus to from Philomythus to Misomyththus, so from the myth lover to the myth hater, uh, and that's who is kind of coding, uh for lewis, who says that you know, myths were, um, you know they're beautiful, uh, their lies, even though they're breathed through silver. So they're beautiful but ultimately they're not true. But what Tolkien was? Apparently this conversation revolved around what is truth in myth, and this was kind of with CS Lewis, where he identifies this as one of his major, I guess, like checkpoints or gates through which he passes in his kind of uh, re-enchantment uh of, of christianity, of um, you know, uh, diaz, um, of him kind of returning to, uh, his you know religious roots. 23:39So, yeah, this is, this is a fascinating poem, and then to have this one here given special attention is, uh, is is great. And to see how it's not just a poem, that he's just spinning this off from his imagination, but it's rooted in when you look at the context, with his relationships with other people and real conversations about meaning and life. And, like you said, julia, he's putting his deepest thoughts into poems. And so this isn't either an academic exercise, isn't just an academic exercise. It isn't just for fun, for kicks and giggles. This is where he's wrestling with the meaning of life in many ways and his own life's work, and that's what I see happening here in Mithipia. 24:24 - Julia Golding (Host)Yeah, it's got a funny start for our era because it's part of a conversation. It starts, dear sir. Yeah, sir, I said, although now long estranged man is not wholly lost nor wholly changed, disgraced he may be yet is not dethroned and keeps the rags of lordship once he owned, man, sub-creator. The reflect, reflected, refracted, get it right. The refracted light through whom is splintered from a single white to many hues and endlessly combined in living shapes that move from mind to mind. So I love the idea that we're all like splinters of light and they move from mind to mind. So what you describe, the star. So if you come up with a great metaphor for the stars, I mean I'm, I catch that splinter and then I see the stars like that. He sees no stars. Who does not see them? First, of living silver made that sudden burst of flame like flowers beneath an ancient song whose very echo, after music, long has since pursued. So the idea is, um, the culture of the myth is so powerful that we all see more clearly in a way. But we see different versions. And of course we all know that white light, the divine light here, is made up of the rainbow. So if we get our red and our orange and our little snapshots. We put them all together, we get back to some, or approach some, sense of the original white light. Anyway, it's a wonderful, wonderful poem, full of thought-provoking images and definitely something a Tolkien fan will enjoy reading. 26:18Okay, let's move on to the section I mentioned at the beginning is perhaps some of the most enjoyable, which is seeing him write the poems from Lord of the Rings. I picked this one rather than the Hobbit because, though there are poems in the Hobbit, I think the Lord of the Rings ones in particular reveal his processes. They were written not all of them, but many of them were written whilst he was working on the book, so they were written for the place in the book that he was going to put them rather than early stuff being brought in. He does that a couple of times, but mainly in situ. They're honed for the position and it's interesting to find out where they fall. 27:03So the notes are very good on this. It points out that you get most of them in the first two books, so fellowship of the ring, and then you get particular outbursts with rohan and the ents, and then after that there is some um, some poetry around the paleno fields, marvelous alliterative verse, and then there's a fantastic short song that sam sings when he's waiting to or trying to find um frodo. So I will give you the first thing I learned from this, which I love learning, which is about poem 149, which is one ring to rule them all, one ring to find them. 27:46He couldn't decide the ring distribution, absolutely fabulous he had no idea how many there were when he was first setting out in the late 30s. He had, oh, is it? Three for the dwarves and nine for the elves, or is it you know? You can see him playing around with just what these rings of power are about. It's absolutely fabulous. I love that because you can literally see him making his mind up in the poem. Of course, that then decides who the Black Riders are and how many there are, and who the rings of the elves were and how many there were, and the dwarves. I absolutely love that. 28:25 - Jacob Rennaker (Guest)I think one of my favorite tidbits about that one in the footnotes is that in an interview tolkien uh recalls that he invented that verse while he was in the bath yeah, lots of bath poems, of course as well. 28:39 - Julia Golding (Host)Um, also in that one, um, there's the delightful note that he used to write out lists of rhyming words. So you know, stone, foam, moan, roan cone and so on. So he'd make a list down the side of the page and then he would look at that when he came to a rhyme. Obviously, you're not going to use roan, as in a roan horse, that doesn't fit. But stone, oh, that's a good one. And he would then put it in, um. 29:09So just to see the poet at work is absolutely delightful, um. So then the next area which I thought was fun to see was the similarity between the way the tom bombadil section of poetry emerged with the Ent of Treebeard's poetry, in a way how Tolkien started writing prose and yet it became poetry, and when Tom Bombadil it slips back to and fro. So it shows you how, as a writer, he's so keyed into the rhythm and the poetry of what he is writing and some of his descriptions are like poems, um, when you actually read them back, you could rearrange them with white space and think, oh gosh, another poem. Um. So I enjoyed seeing that being really sort of lifted out of place and examined yeah, that was a good one. 30:05 - Jacob Rennaker (Guest)I appreciated that too, that, and there was some in the reworking of oh, it was later, uh, I think it was. It was legolas's poem, um, yeah, the song of legolas, where he so in in between some of his he had, you know, several different reworkings of of of this poem, uh, and in one of that reworkings then he then adds a prose passage, kind of like in between that. So it's really like, so his the prose was inspiring the poetry, but also it would go both ways, and sometimes you're like you were saying it's hard to tell the difference between the two. It's a, it's, it's. The prose is written on such an elevated register and the rhythm is such that you could break it out, and sometimes you see him trying out different. You know ways of indenting, right, how are you actually breaking up lines of the poetry? So it's very a fluid process for him. It seemed that that he was being inspired. There's this, you know, yeah, again, like this ebb and flow of, like this idea. Is this an idea that is, uh, communicating itself better in poetry or in prose? 31:10If it's in poetry, and one of the things that he goes, uh, you know, makes a point of is that these aren't just mere decorations, that these are. The poems are integral to, uh, the the story itself, because he's not just, you know, inserting a poem for poetry's sake. It has to serve the plot, um, it has to clarify the thoughts and feelings of the individuals, um, it has to help distinguish between the different races that he's talking about, that he's developing. So dwarf poetry is going to be different than elvish poetry is going to be different than hobbit poetry is going to be different from, you know, gondor rohan, they're all going to be different than Hobbit poetry is going to be different from, you know, gondor Rohan, they're all going to feel different. So it's part of creating more of the texture for this world and it's going to advance the plot in some way. 31:55And so this is where I think it's kind of comparable for those people who follow the history of musical theater, that before the in America, before Oklahomaoma, the play, there were just, you know, there would be a story and then kind of like breaks for just kind of like song and dance and they do that and then kind of get back to the story, but starting with uh, with oklahoma, that was where the characters would stop and actually sing about what they were thinking and feeling as an aside, and it would further the plot. And then, from that point then, the pattern for musicals was the, the, the musicals and asides had to serve the plot, or that was one of the primary purposes of this. It wasn't just a break from the seriousness of this, it was actually incorporated into there and Tolkien is like it's very much doing that, that this is he's taking such great care to, to make these poems distinctive, uh, and consistent with the rest of the mythology. Um, and so he. These are doing so much work and one of the points that the authors, um, or our editors of this volume make is that a lot of the fans or there are, I won't say a lot, but there are people among fans of lord of the rings and the Hobbit that just kind of skip those, probably more in Lord of the Rings, that they see the poetry as an excuse to just kind of skip to the next prose section. 33:14But if you do that, you're actually missing parts that are central to the story itself and the enriching of the world of Middle Earth. 33:25So slow down so when you get to poetry, rather than kind of speeding up and just trying to get along your way. One of the things I think that this book demonstrates is the need to actually slow down when you get to the poetry to then say, okay, why did Tolkien write this as a poem, rather than just, you know, say Aragorn sang a song and then move on. He's actually goes to quote it so like, why did he do that? And if you take the time to read it, then you kind of see, and what this, what this volume does is, lets you behind you know the curtain, to see tolkien's process of how seriously he took it and how, how much development he's doing that, how much heavy lifting the poetry is doing for his world building, for his character building, um, and it's just, it's just phenomenal once you get to see what's actually going on here yeah, and the editors do a wonderful job too at connecting poems to their external context where that's relevant. 34:21 - Julia Golding (Host)So I enjoyed reading about um, the wizard from the calabala, who has the tom bombadil, or the other way around tom bombadil has the power of song, such as the wizard from that beloved work that tolkien loved, um, a great finnish epic, isn't it? I think? Yeah, all right, um. And also but not just things back in the past it mentions that the lament for Boromir has resemblance to a well-known to Tolkien's generation poem by Kipling, who was probably the preeminent poet at the end of the Victorian era for most people. So that's interesting, and of course it's very different from Kipling, but yet to find those echoes's interesting, and of course it's very different from Kipling, but yet to find those echoes is interesting. I have a particular enjoyment of the evolution of the Prophecy Song. Now, for those of you who have come at this from just watching the films, you missed this because they leap over the Grey Company. Um, they, they leap over the the grey company, but anyway, um the grey company arrive when aragorn is trying to work out how he can get to ministerius in time to save the city, and they come bearing another prophecy. There are several prophecies, nudges, oh, from the, from history or dreams telling people what to do, and this one is the one about the Stone of Erech. He has to go, and the Stone of Erech would be a very different thing, the Stone of Erech. He has to summon the army of those who didn't fight for Isildur his ancestor, and what I really liked about this is seeing that his first thought was, originally the prophecy would begin to start being fulfilled because three lords would be present to summon them, and the three lords are obviously Aragorn, but Legolas, who is the son of a king, and Gimli, who is a son of another very notable dwarf. So they were the three lords there. 36:32But Tolkien moved away from that, and what he did by doing that is he left it open that they may choose not to fulfill the prophecy. At this time it wasn't sliding down to inevitably. Oh well, the three lords have turned up. So therefore, this is the moment he. He cut that out and made it simpler. So there's more jeopardy at the moment. 36:54And a very similar thing happened to um, poem 153, back in um, fellowship of the ring, where the hobbits are singing one of their walking songs and it mentions that the ring is going to be cast into the fire. Hang on a minute, they don't know this. So he takes that out so that the hobbits at that stage think they're just walking to Rivendell, and it makes Frodo's decision to be the one to carry the ring from there to Mount Doom a much bigger deal. So those particular evolutions of the poems were fascinating to see how he moved away in a good, productive way from his first thoughts to simplify the poems and take out any plot spoilers which weren't necessary or helpful at that point. Yeah, do you want to say anything about the? 37:47 - Jacob Rennaker (Guest)um, the wonderful alliterative verse in the rohan battle of paleno field section yeah, this is yeah, and these are really interesting and I think you see a lot here of of those, especially, like I mentioned earlier with with rohan, that his academic studies, right, his profession, uh of you know professor um dealing with you know anglo-saxon literature, old english, that that really colors, uh, his interpretation of you know these these events that he is himself creating and so he has these stories and then he's, you know, coming in and playing the bard afterward you know, recounting uh these these events and doing so in a way that he feel would be lived in an in-world um, uh, and so, yeah, so I I it mentioned that there was, you know, a particular uh poem that he was drawing from. Uh, the wanderer uh was one of these poems uh, that he that was the for the where now the horse and rider um is. That is that the particular one you're talking about? 38:59 - Julia Golding (Host)well, there's several, there's a few so all the alliterative verse. 39:07So some of them are pre the battle and then some of them are accounts of the battle and the sort of roll call of the dead. I think one thing that struck me is how this links back to that poem. I mentioned at the beginning, the brothers in arms, because that's got a feeling of a similar idea of people being buried under the swelling grass. He fell alone. I heard him cry. I could not reach him, save to die Too late. Beside him let us lie, make him a grave beside the sea, heap the same earth over me. There together let us be build our barrow broad and high, that homeward sailors passing by may mark the headland where we lie silent as long as time shall be, in narrow house, without a key and so on. 40:04So surely when he's writing these laments he was already using the idea of barrows and the old Anglo-Saxon burial practices for his real loss of his real friends back in the end of the First World War writing the laments for the dead Pelenor Fields. I think there's more power knowing that he lost friends in war and it's a very fitting, beautiful way of marking that. I always find it incredibly moving that list of names. I was reading it this morning I had tears in my eyes and I've read it so many times. We don't really know anything about the names mentioned there, but I just find it really moving the list of people. It's like looking at the names on a cenotaph or on the wall of a church. We've got one in our little village church with the names of the lost. Look at it every Sunday. 41:14 - Jacob Rennaker (Guest)It's a similar powerful effect. Yeah, that is absolutely true and I think, and that's something that uh also comes across in like greek literature and something I noticed in my most recent like reread of the iliad um was, you know, seemingly randomly, there'll be some person called out and it says this person and then gives like a line and they don't have any sort of role within the larger narrative but they were just, you know, uh, tom, who, who showed up, who was conscripted into service and he, you know people really liked him, he had, he had people over to his house and he made him feel good, uh and like, and he died, and that that's tragic. So, like when I would see these little individual names in that those lists called out, it was, it was the, the anonymity in some ways that lent a greater weight to that character, um, that, yes, this was a person, but there's, you could tell that, okay, this person had a life, right, this person was what was valuable just for being a person. And here they were, they died in this. So it's tragic in that sense, but in another sense, they are being memorialized for ages to come because they were part of this heroic battle and that's something that I think Tolkien we see, as he's looking at the differences, he's playing with some of these old English poems. 42:32In some of them he's seeing the tendency being just kind of more downward, toward despair and pure lament. But in the reworkings of these different poems, or his sparring, his engagement with, he always kind of adds some ray of hope. There's something that is kind of worked into there that adds and even if though they died, there is something either beautiful about their death or something that's hopeful in moving beyond the death of that person, even if it is just the memory of their life. That that's something that can, you know, overcome this kind of chasm of death that's been created by the death of this person. But that light can be drawn forward, and it's drawn forward in these kind of epic traditions. That's. 43:19 - Julia Golding (Host)That's just beautiful to me and I would say at this point that if you are a bit cold to the paleno feels poetry, immediately run away and go and listen to the BBC dramatised version where they have an absolutely brilliant setting to music of this. It's fantastic and it shows you how powerful the poetry is if you imagine it sung. And it's so well done. In fact, a lot of the poetry is done brilliantly in that bbc adaptation from the 80s set to wonderful music, so highly recommended. Okay, so, um, just sort of finishing off on the lord of the rings material, before we give our verdict, I would say that my favorite poem of them all is the one that Sam sings when he's in Curious Angle in Western Lands Beneath the Sun, that one Beautifully sung by Bill Nighy in the BBC version, and it's a song I used to sing to my kids as a lullaby. 44:21Oh sure I'm a real Tolkien keen. They get indoctrinated young in our household. Well, tolkien Keane, they get indoctrinated young in our household. And I was fascinated to watch the evolution of my favourite poem, because it started out much more complicated, more lines, more verses. It kind of morphed into the Bilbo. I sit beside the fire and think it became a bit more like that, as though it was a bilbo song. And then it became for me. If you, if you want someone to say to you what is the essence of tolkien poetry? It's this. So the first verse is about the beauty of middle earth and the stars in the sky and the trees, and then the second verse is defiance. Though here, at journey's end, I lie in darkness very deep. That bit, um. So it seems to me like a little perfectly formed summary of everything that's brilliant about tolkien. So there you go. That's worth the price of the admission, isn't it? How about you? Have you got a favorite poem? 45:26 - Jacob Rennaker (Guest)I think, yeah, I just kind of want to echo that one. I think that was for me looking at him reworking that one, and that's really where it hit home to me, his revisions, because at the earliest versions of that it was, it was really a lament, it seemed like uh, but then, as it's slowly being revised, it has this upward curve, yeah, uh, that's towards, even though they'll start with like the beauty, but then it still. It was like and now, you know, the world is dark, you know I'm in a sea of shadow, or I'm uh, you know it was one of the phrases that ended up being used. Um, and so from being just kind of lament, pure lament, to then this you know upward turn that you're still, the sun is still shining above the shadows. 46:10 - Julia Golding (Host)Right there's a sun. 46:11 - Jacob Rennaker (Guest)And stars shall ever dwell yeah, see, that's and that's, but then that wasn't in the earliest versions, right? 46:16So you see tolkien almost going through this, this evolution that you see, um with, I think himself, even with, like war poetry, with seeing, you know, being bogged down by here's, this death and this, you know, inequity and destruction of both human life and the natural world, right, with industrialization and this. 46:38You know this long defeat, but you see, then you know that there is this hope, this belief in something that can transcend that. And so you kind of see in this poem a microcosm of Tolkien's kind of personal evolution. And I'm wondering if I think this poem I think is a great way to kind of end our discussion about his poetry, because this poem itself, our editors, point us to a legend, english legend of a minstrel who is searching for King Richard I of England and who went around, wasn't sure where the king was being kept, and so the minstrel would go and sing this song and wait for the response to the following verses and went from castle to castle until finally he heard the responding verses and knew that's where the king was. And so Tolkien is playing with that idea, and they can say that because he mentions that episode in a letter to somebody else, so they knew that he knew about it. 47:39 - Julia Golding (Host)Well, I knew about it. Outside of this, anyone who reads kind of myths and legends here the bard's name is Blondel one who reads kind of myths and legends here uh, the bard's name is blondel. And uh, richard the lionheart managed to get himself quite a good pr in history. He wasn't actually a bad guy, but he's. He's done quite well. 47:56 - Jacob Rennaker (Guest)He's the good king in robin hood the disney the disney film apparently he wasn't really folks, sorry, but anyway, in the myths and legends he comes out well and um, indeed blondel um locates him by singing a song outside his window so, yes, you have like, yeah, so this is informed, so the story, so it's not, you know, again, like aping, it's not just a wholesale copying of it but it's taking that idea and recasting it as the seed for something beautiful that's happening here. So you have that kind of the academic engagement with story and tradition. Um, you have his kind of like personal evolution of, uh, you know how he's dealing with death and loss, um, and also, I, I think maybe even for his own creative process, um, uh, and and this is, I'll quote this from right from from lord of the rings, it's kind of like, right before the the poem, uh, he launches into the poem. It kind of talks about how sam starts, kind of like spinning up to, to say the poetry, uh, it says um, to his surprise, uh, to sam's surprise, right moved by what thought in his heart he could not tell, he begins to sing. 49:03Uh, he murmured old childish tunes out of the shire. So he starts with picking all these, you know, nursery rhyme songs that he heard and snatches of Mr Bilbo's rhymes. So Bilbo was taking these elvish poems that he'd learned and the dwarvish poems and he would share those. So from the larger world they weren't simply childish tunes or nursery rhymes. These were ones that had more of an more of a bit of an adventurous epic field to them. So he has, you know, childish tunes out of the Shire. He's murmuring, he takes snatches of Mr Bilbo's rhymes that came into his mind like fleeting glimpses of the country of his home, and then suddenly new strength rose in him and his voice rang out while words of his own came unbidden to fit the simple tune. 49:45So he's taking these simple ideas, but then his own experience and thoughts are kind of then giving content to that general form that he is in a sense purveying, because again he's honoring those songs and everything that came before and then adding to that being a participant of that, not replacing them, but being a participant in that, just like you see, with you know, with their discussion between Sam and Frodo, that we're all part of the great story, right? You know what, if somebody would say you know about the same things about us, would somebody ever say a story or write a poem about us? It's silly to think of, but then like, well, they would have thought the same things in their time. But after you know, you know in retrospect, and having developed a maturity, you can see that your own life is something that's worthy of poetic. 50:33You know, uh, reinterpretation of um, and that's something in this song. I think it is kind of a microcosm for everything. Great that we see about tolkien's process as a poet, uh, as a creator, right, as an artist, uh is all is all right here and we have this book, um, it's wonderful collection to thank for this kind of peek behind the curtain to see into right tolkien as, as an artist, as a, as a human, um, uh, and his whole experience, and it's just, it's just wonderful, highly recommended, uh, worth, worth its weight in gold so the verdict on the three volume is five stars, with the caveats we said. 51:12 - Julia Golding (Host)It's not an easy read, but it is a really fascinating read and I think that I came away thinking well, I wouldn't say he was a great poet of the 20th century because so much of the poetry is connected, connected to the specific world. But it makes him a great narrative poet. He's innovative, he's got a variety of registers because of the cultures he's exploring and he also captures a sort of jewel-like intensity about the world, literally often with the words of jewel. So you, I think the atmosphere he creates is beautiful and fascinating, particularly good on the natural world. He does this with fairly simple words, simple nouns, natural images, powerful rhythms, and they make great songs. So I think he's I think he's the best poet who is a novelist, if you see what I mean a poet within a novel. I think that's where I would put him. 52:17 - Jacob Rennaker (Guest)Yeah, agreed, yeah, it's nothing that you would put aside. Other poets, historic poets, you wouldn't put it next to. Well, I might put them next to Homer, just because Homer was, was writing with myth as well, right, uh, but if you're looking at just you know, at at at poets like contemporary poets, um, it's not, it's not the same. This is something, like you said, julia, it's. He's doing it within the context of this larger myth, and so I think of of stories read within fictional worlds and poems that are part of whatever fantasy novel that I've read. This certainly is the top. This is kind of the sterling example of what thoughtful integration of poetry can do for a work of fiction and a work of art. 53:12 - Julia Golding (Host)Okay, so just a sort of deep breath and we're going to leave Middle Earth now. And just to finish with our where in all the fantasy worlds? Question that we try to land on in Mythmakers when in all the fantasy worlds do you think it'd be good to be a poet who is writing the elegies and the laments, because I feel that that's a particularly strong vein in his poetic collection? Where would you think it'd be really great to be a poet of the, the dirge or the elegy? 53:49 - Jacob Rennaker (Guest)Yeah, yeah, no, this is that's a. 53:51That's a great question and I think, as I was, I was thinking about it, I might have nodded towards this a little earlier. 53:57I think the Trojan war, the, the, the in the Iliad, and there's and, by the way, if you're, if, if you haven't read the Iliad in a while or you were forced to read it as a student, there's a beautiful audio version of it. 54:15Alfred Molina is a classically trained Shakespearean actor and movie star in his own right in film, but he does a wonderful, wonderful reading of the Iliad, and so that's really, I think, where I learned to appreciate the Iliad more was then going back to it after a while and then listening to his recitation essentially of it, understanding that, the poetry of death, of war, and what Homer was able to do there. So if you're looking at the quasi-semi-mythic historical world of the Trojan War as presented by Homer, I think that that's one that just their view on death the good death was beautifully captured in the Iliad are certainly fictional and mythic elements there that it'll be close enough for me to say that I would choose, uh, choose, yeah, a bard, uh, that's with the Greek, uh, or Trojan armies, that's recounting the the loss of their, of their soldiers yeah, I guess that you know. 55:44 - Julia Golding (Host)When you ask that question, you think well, what would it be like in Alice in Wonderland? You end up with a comic poem, don't you? So I was wondering to think of a world which could do with some lament poetry, and I was thinking, actually, star Wars, okay, could do with some, because they've got some great themes provided by John Williams, but I don't remember them really focusing much on culture. 56:12 - Jacob Rennaker (Guest)No, so it'd be quite. 56:15 - Julia Golding (Host)It'd be really interesting to have someone give it some serious thought about. You know, the lament for the death of Han Solo Sorry, that's plot spoiler. That would be really interesting because you could then combine it with the idea of the force and yeah, what lives on. So that would be, I think, a really fascinating place to be a writer of laments that's and you know what. 56:38 - Jacob Rennaker (Guest)And then, speaking of that, like there is, uh, and if you want to bring in, uh, a you know tip, something to read, there are two different poetic reworkings of star wars that I need that now, julia, you've inspired me to go and and look at uh, one of them is william shakespeare's um, uh, star wars like barely, uh, a new hope is the first, the first one that came out, and so it's so it's fully re, you know, reworked into iambic pentameter, uh, and there's some very clever things that are that he does there. I want to see what some of those death themes, if the author there actually goes into some of those you know elegies. So there's one. There's also another one that is the Odyssey of Star Wars, and so it's more in the, you know hexamic dactylator, right, right with, with, yeah, so it's. So it's more done in, you know, classic greek form as opposed to, uh, you know a british, you know contemporary with you know shakespearean. 57:36So I want to check especially the kind of homeric reworking of star wars to see if how they treat the death scene. So, thank you, thank you for for bringing that. I think that is fascinating. I want to see if somebody does that. But you're absolutely, absolutely right that that and I think that's what with Lord of the Rings, that's one of the things that gives it its depth is that death is treated as something that is serious and worthy of reflection and sitting with, and that's something you don't get everywhere. 58:00 - Julia Golding (Host)Yes, and perhaps we'll report back if we find something Okay. Thank you so much, Jacob. We've been talking for a while, but it is a big subject, surprisingly large for most of us who didn't realise that Tolkien was such a poet. 58:20 - Speaker 3 (None)Thank you very much for listening. Thanks for listening to MythMakers Podcast brought to you by the Oxford Centre for Fantasy. Visit OxfordCentreForFantasy.org to join in the fun. Find out about our online courses, in-person stays in Oxford plus, visit our shop for great gifts. Tell a friend and subscribe wherever you find your favourite podcasts worldwide.